Dororo, vols. 1 and 2

Dororo, vols. 1 and 2

By Osamu Tezuka

Vertical, Inc., $13.95

If Viz published Dororo, they would put the scrappy title character front and center, fists flying as he dispatches yet another evil spirit. But this edition is published by Vertical, purveyors of fine classic manga for adults, so the covers of these two volumes look like they were designed by Joseph Cornell—if Cornell had had access to neon inks and spot varnish.

At its heart, though, Dororo is a shonen manga. The two main characters are knit together in a grudging friendship. They travel through samurai-era Japan, encountering all sorts of enemies, from spirits of dead babies to wicked feudal lords, and dispatching them all with a combination of skill and ingenuity. And along the way they come to terms with the circumstances of their lives and find a purpose for their wanderings.

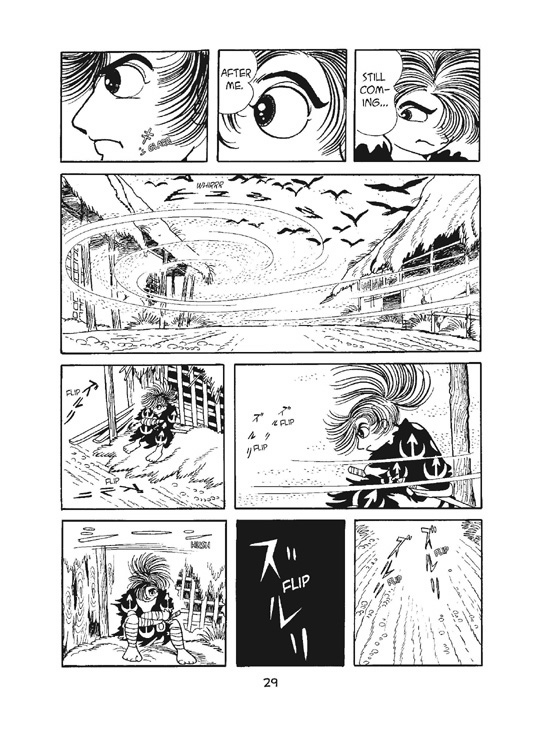

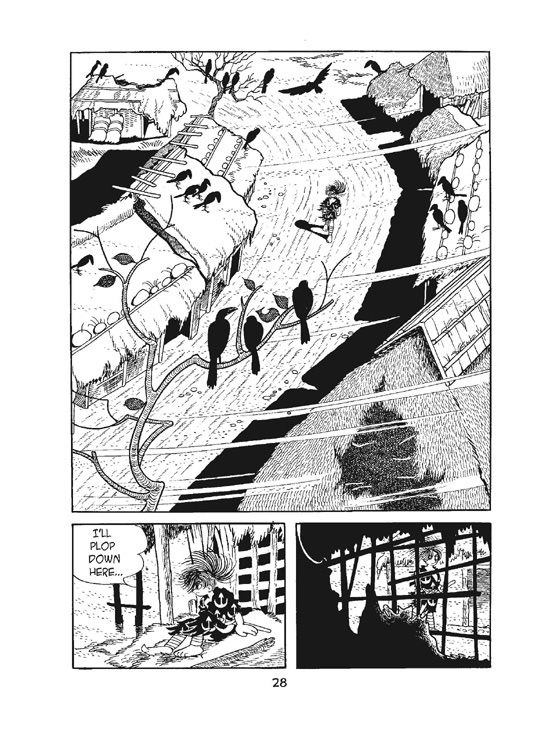

What lifts Dororo above the ranks of the humdrum, of course, is Tezuka’s storytelling and his art. I know we’re all supposed to like Tezuka because he’s the godfather of manga, but often I find his work awkward and overly stylized. Not this time. He stretches his panels out to accommodate a whistling wind or a swarm of snakes; he zeroes in on a figure, a face, an eyeball; he depicts sweeping landscapes and interior states of mind with the same attention to detail. This is a book worth buying for the art alone.

Hyakkimaru, the main character, has had a most unfortunate beginning. Before he was born, his father, an evil nobleman, cut a deal with 48 demons: He gives each of them a part of his unborn son, and in return, he becomes the ruler of the land. Indeed, Hyakkimaru is born blind, deaf, and limbless and at his father’s command, his mother sends him off down the river in a basket to die. In typical manga fashion, he is rescued by a wise old man who comes to love him as a son and who fashions prosthetics to replace his visible missing parts. Handily enough, the prosthetics all double as weapons—his arms are swords, his fake leg shoots out caustic powder, even his false nose contains an explosive. Hyakkimaru is blind and deaf but has strong intuition that not only replaces those senses but also allows him to sense the presence of spirits of the dead, who seem to follow him everywhere.

Hyakkimaru’s traveling companion is Dororo, a little kid whose most compelling characteristic is his ability to absorb horrific beatings and keep on going. Dororo is scrappy and selfish, which is not surprising once we learn his backstory, but he also has great compassion for those who are beaten down by life. Hyakkimaru is older, wiser, and more skilled, but still not sure of himself or where he is going, at least at first. His journey gains meaning as he proceeds, and each time he defeats a demon, he wins back one of his missing body parts, becoming whole literally as well as metaphorically.

Dororo is very episodic: The two characters meet their enemies one at a time, and each encounter is different from all the others. Hyakkimaru is a skilled swordsman who relies on his intuition as much as his bionic weapons. Dororo gets by on sheer grit and a complete lack of respect for any authority. Tezuka comes up with an imaginative array of foes: A god who steals his victims’ faces, a feudal lord who kills anyone who crosses his border, a moth-woman who kills to preserve her secret. The stories are different enough that the book never feels repetitive or formulaic, and as these two volumes progress, Tezuka reveals more and more about his characters, so Dororo is more than just a collection of adventures, it’s a real story.

What is rather jarring is the juxtaposition of brutality and cuteness. Dororo is rounded and adorable; he could have stepped out of a Betty Boop cartoon or a classic Disney movie. He acts like a cartoon character as well, all double-takes and exaggerated gestures. So he doesn’t look right next to a firing squad, and when he calls a nobleman who has just killed two children a “poop snake,” it doesn’t really sit well. There is a lot of graphic violence in this book, and the fact that most of the victims have cartoony features doesn’t mitigate it. This isn’t Wile E. Coyote getting hit on the head with a giant hammer; it’s parents being shot with arrows as they plead to see their children one last time, or innocent workmen being beheaded so they won’t betray the details of their project. Less unsettling is the revelation that Dororo, whose feistiness is played mostly for laughs, has a sad backstory; that does seem to fit with the character.

Dororo was first published in 1968, and the art does look a bit dated. Hyakkimaru’s wild hair, Dororo’s chubby features, and a cast of characters that look like Asterix extras in Japanese costumes take a bit of getting used to. Unlike many modern artists, though, Tezuka pays attention to detail, and the backgrounds and settings are often breathtakingly beautiful. His battle scenes are staged with attention to the psychological tension as well as physical action, and his depictions of supernatural creatures, even the repulsive ones, are fascinating. Undergirding all this is a panel structure that really serves to move the story along: huge panels setting the scene, quick actions or turns of mind chopped into small squares alongside a vertical panel that shows the context, horizontal panels stretching across the page to slow down the action at the end of a movement. This is a book well worth buying for the art alone.

Vertical, of course, gives this book the star treatment, with creamy, high-quality paper and covers that won’t make adults embarrassed to carry this book in public. There is one problem, although it’s obvious only on close examination: All the lines and even the lettering in the balloons have a slight stairstep effect, to them, as if they were shot through a screen. The early pages of vol. 1 are also marred by some moiré in the screen tones, but as Tezuka doesn’t use much toning, this only occurs in a small part of the book.

Although it probably will never sell in Naruto-like numbers, I’m glad Dororo isn’t printed on newsprint with a scrappy Dororo kicking someone on the cover. Tezuka’s art and storytelling skill make Dororo a delight to read, a good example of a classic that deserves to be a classic, and Vertical’s presentation only enhances that.

This review is based on complimentary copies provided by the publisher. Images copyright (c) 2008 by Tezuka Productions and taken from the Vertical website.

Dororo is the first Tezuka I’ve read, and so far I’ve liked it quite a bit, volume 2 even more than the first one. One thing that bugs me is how often Dororo calls Hyakkimaru “bro.” I wonder what word he’s using in the original—aniki? Nii-san?—and wish Vertical would’ve just left that intact and included a translation note.

i loved dororo as well. the day i bought it i immediately got caught in a bad rainstorm and crimped the book up a bit, so i can’t really comment on the paper quality. as much as i hate that i didn’t make a better effort to save them (i had a book bag with me, and i could’ve even just folded the plastic bag they were in over once or twice), i know that i’ll never see them in-person again, so i’m thankful i found them at all.